A Guide to Brain Emulation Models

The march to digital brains, explained for the curious.

By Maximilian Schons, MD

Preface

Brain emulation is the replication of brain processes at high biological accuracy on computers. If anything, it received substantial skepticism from the pragmatists of this world. Some critics might say, "We've had the worm brain diagram since 1986. Still no convincing digital worm. How can we possibly hope to get anything bigger than that?". Others will point to the Blue Brain Project, an effort to make a digital simulation of a rodent brain. Blue Brain began in 2005. Later, related goals were incorporated into the EU's Human Brain Project (launched in 2013 with roughly €1 billion over a decade). Initiated in 2005, the project advanced useful tools and data, although several of its original goals proved harder to reach than expected.

The context in 2025 is very different from when the Blue Brain Project started. Back then, there wasn't even a single computational model of a worm. Now, we have reconstructed insect brains, gathered much richer data from many organisms, and various brain model prototypes exist.

I base this assessment on a comprehensive report I had the pleasure of leading. The "State of Brain Emulation 2025" (SOBE-25) summarizes months of research and many expert interviews. The co-authors are amongst the sharpest neuroscientists I've met:

Niccolò Zanichelli, an Italian computational biologist.

Isaak Freeman, an Austrian PhD candidate at the MIT Boyden Lab in Boston.

Dr. Philip Shiu, who as a postdoc at UC Berkeley created a simulation of the fly brain using the Drosophila connectome.

Dr. Anton Arkhipov, who has led mouse brain model development at the Allen Institute in Seattle for years.

The audience of this guide is anyone new to the topic of brain emulation. I took the liberty of summarizing, illustrating, and contextualizing the State of Brain Emulation Report 2025. I gave my best to make it as accessible as possible and share my personal opinions too.

The best way to approach this guide is just to follow the order of chapters:

What is brain emulation, and how does it differ from AI?

Why try to model the brain on a computer?

Where are we today with brain emulation technology?

What gaps exist for good brain emulation models?

Next steps for brain emulation models.

Readers should budget at least one or two hours. For a lighter start, please refer to my Appetizer for Brain Emulation Models [Link].

This guide also refers multiple times to a comprehensive data repository we created for the report. It also comes with previously unpublished figures and a budget template for reconstructing brain wiring diagrams.

Views and mistakes are all mine. Necessarily this piece will have biases and omissions. Available evidence today remains is limited to millimeter-sized organisms, so any generalisations to larger brains are speculative. Also note that some factors had to be omitted completely. These include non-neural influences such as hormones and glial cells, details on behavioral data collection and neuromorphic computing. More generally this piece focus is explaining the science and does not try to opine on ethical, legal, and societal implications.

I wish you fun diving into one of the most fascinating topics of my life.

Best,

Max

October 2025

I. What is brain emulation, and how does it differ from AI?

Large Language Models like ChatGPT may reach human‑scale intelligence by imitating us. Yet they are not digital human brains.

| In short: What is brain emulation?

Emulation: Aim to accurately recreate internal architecture, which in turn generates outward behavior. Simulation: Aim to just match outward behavior without reproducing the internal architecture. Brain Emulation Model: A computer program that mimics how a biological brain works. It models the information processing by neurons, for instance by replicating connections between neurons and their electrical activity. Biologically Faithful Brain Emulation: We define it as a model that demands high accuracy in several biological areas. A reconstructed wiring diagram of all neurons with high resolution modeling of neural electrophysiology. In addition, various neural and non-neural cell types, and chemical signaling systems. Brain Emulation Pipeline: This is the full process of taking data from organisms and using it to model brains on computers. It includes in-vivo neural recording (Neural Dynamics), ex-vivo brain mapping (Connectomics), and Computational Neuroscience. LLM (large language model): A computer program that imitates human skills without brain‑like mechanisms. It uses large statistical maps to predict the next words in a given context. Examples include the applications ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude. |

|---|

We already achieved one form of digital Intelligence. Modern large language models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, have now surpassed humans in many cognitive tasks.

Train modern LLMs on extensive data about your writing, speech, or behavior patterns, and they will excel at imitating you. The more data you provide, the better the next-word predictor matches your word choices, preferences, and opinions.

LLMs don’t work like our brains. Instead, they use a very different architecture of a massive probabilistic prediction engine. LLMs are trained on text you provide, often crawled from all over the internet. They start off with random parameters, also called weights. Machine learning algorithms then update weights if predictions don't match the original data; an iterative process known as backpropagation. And the more you scale up this training process, the better the predictions get (see Figure A).

Neuroscientists have been iterating for decades on a fundamentally different approach. Their models rely on more or less accurate representation of our biology. Rather than just imitating behavior, they aim to replicate the underlying architecture. This requires bespoke neural tissue data, produced only by a few thousand laboratories around the world:

Neural dynamics: recordings of neural activity. Ideally with controlled manipulation of neural activity and parallel recording of behavior.

Connectomics: information about the connections between neurons. Ideally with molecular annotations of structures that matter.

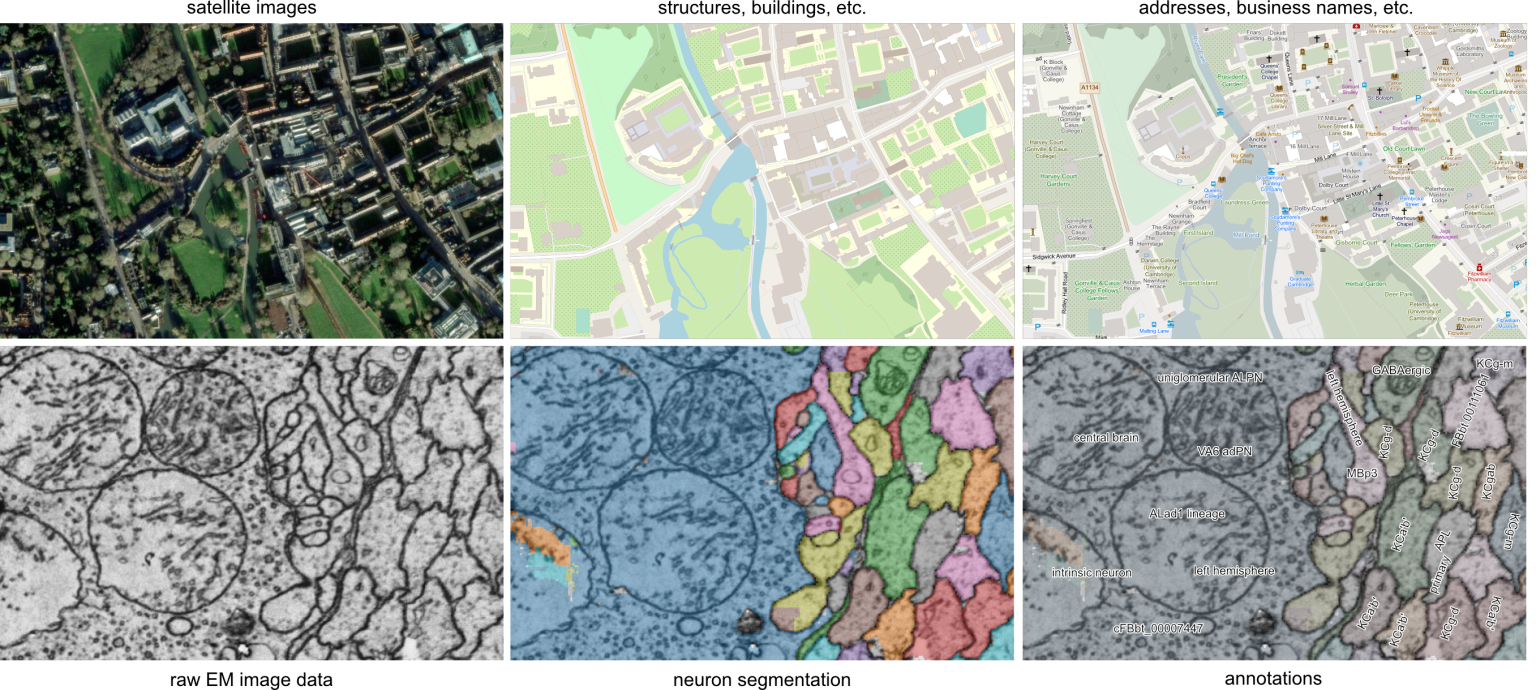

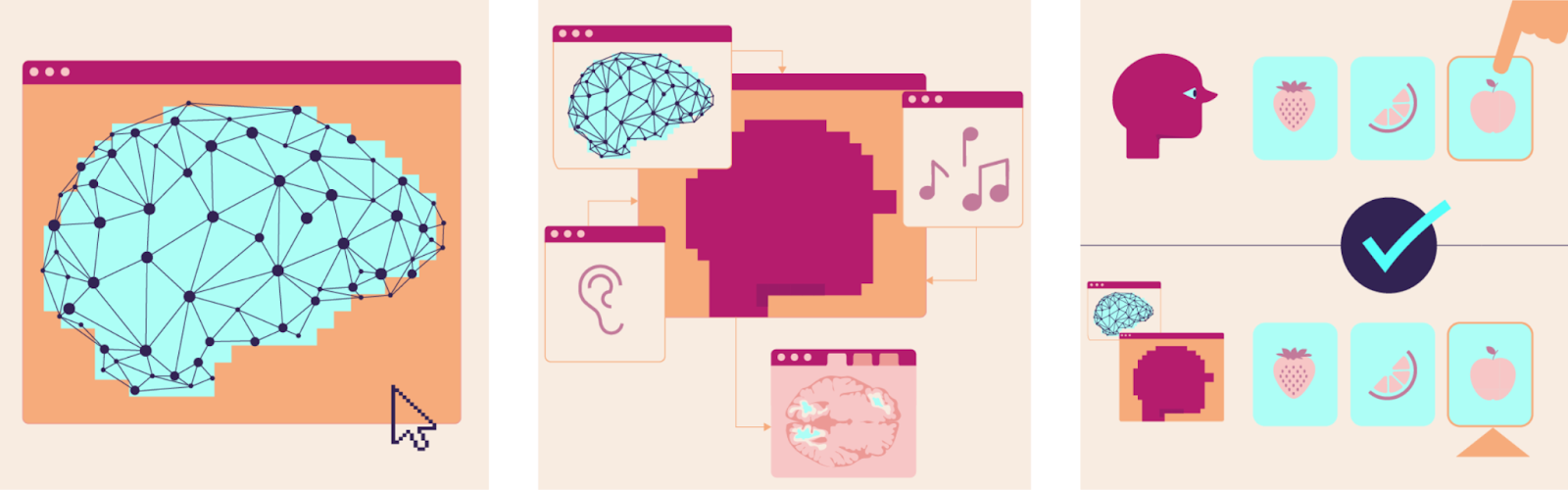

Computational neuroscience leverages this data to create brain models. Connectomics provides the information for how to connect digital neurons to a broader network, neural dynamics how neurons process information (see Figure B).

Figure: Comparison of Large Language and Brain Emulation Model Pipelines. A) Large Language Models feed text or other filetypes to model weights that predict the next step. Prediction and original are compared. The error is used to update parameters in a process called backpropagation. B) Neural dynamics include different brain activity and behavior recording methods. Connectomics stepwise scans brain tissue to reconstruct a map of all neuronal connections. Both inform how to construct and tune computational models of the brain.

Machine learning models might finish a sentence like a human would, but their internal architecture is very distinct from how our brains would do that. While machine learning researchers sometimes use similar terms, their “neural networks” have very little in common with actual brain tissue. Because of this difference the technical term that describes modern LLMs is simulation. Just replicating behavior, without the underlying architecture. Large Language Models are widely successful brain simulation models.

Neuroscientific brain models however are computer programs that pride themselves by emulating the structure and activity of a brain which in turn give rise to behavior. No difference in architecture - a digital replication of as much physical detail as possible and necessary. Those are brain emulation models.

The following table provides some additional context. I list evaluation criteria for the quality of brain emulation models we also used in the SoBE-25 Report. The higher a computational model scores, the stronger the case for calling it a brain emulation. Lower levels are simulations, basically detached from biological reality. That is what LLMs represent today. Biologically faithful emulation represents high levels of accuracy across domains. As Sandberg and Bostrom already noted in 2008, there are almost arbitrary levels of resolution beyond that1: from spiking neurons to random movements of every molecule. And maybe that is still missing something. Independent of the biological accuracy axis there is also the behavioral accuracy axis - behavioral repertoire, timehorizons, memory etc - which we will touch on later.

And with that, let’s take a look at the pipeline, data output, and actual brain emulation models in more detail.

Table: Biological Accuracy of Brain Emulation Models - Accuracy across distinct biological dimensions.

| Scale modeled | Brain realism | Neuron realism | Neuron adaptation | Timing precision | Cell variety | Hormones / modulators | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation (e.g. LLM) | Tiny circuit or no brain | Random connections | Undefined units | Fixed connections | No time steps | Single neuron type | None |

| Simple bio‑inspired | One brain area | Simple connection rules | Non-spiking neurons | Short‑term changes | 100s of Milliseconds | Excitatory and inhibitory neurons | One modulator |

| Complex bio‑guided | Most or all of the brain | Complex connection rules | Spiking Point‑neuron | Medium-term changes | 10s of Milliseconds | Variety of neuron subtypes | Multiple modulators |

| Faithful emulation | Whole Brain [with virtual body] |

Wiring diagram of actual brain tissue | Spiking multi‑ compartment neuron |

Full growth and pruning of neural connections | Milliseconds or less | Diverse neural and non‑neural cell types | Interacting modulatory systems with feedback |

| “Complete” Emulation | Arbitrary degrees of resolution across all dimensions | ||||||

Since there is no official definition, for the remaining piece I will be using a working definition I call biologically faithful brain emulations. Think of the following components as a lower bar for genuinely replicating the brain:

Verified wiring diagram of all neurons

Diverse neural and non-neural cell types

Complete growth and pruning of neuron connections

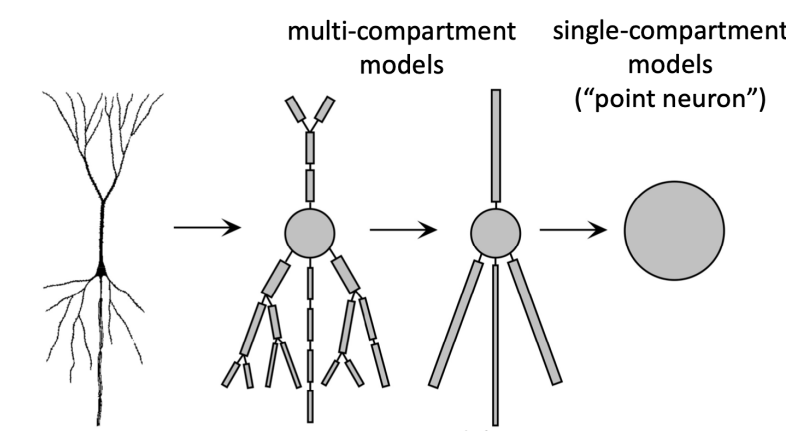

Detailed multi-compartment neuron models

Interacting neuro-modulatory systems with feedback

Millisecond time frames

Embedding the digital brain in a virtual body

Many of the terms might feel foreign at this point, but we will address them in the upcoming chapters.

II. Why model the brain on a computer?

In the past ten years we estimated that about $8 billion was spent globally on basic neuroscience excluding brain related medical research (see this table; note that it). While that sounds much, Apple has spent 25 times as much over a similar period on R&D.

The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the largest neuroscience funder globally. Their mission is to improve national health and ensure a "high return on investment for U.S. taxpayers" (NIH, 2024). The logic is sound: beneficial outcomes could range from therapies to high-skilled jobs.

To appreciate the scale and possible returns of these investments: the Human Genome Project’s economic return was an estimated 140-fold on the $8B investment. It also created over 300,000 jobs and transformed drug discovery (Tripp and Grueber, 2011; Gates et al., 2021). Similar stories can be told about many other science-focused initiatives. The Apollo program returned a 7-8 fold on an estimated $300 billion investment (inflation-adjusted; Dreier, 2022; NASA Spinoff). DARPA-net and CERN sparked a trillion-dollar Internet economy.

Will we be able to make such an investment case for brain emulation models? To attract funding, the brain emulation community must point to clear value propositions beyond basic research. Let me share some candidates.

Why model the brain on a computer?

Fruit flies walk, fly, see, and smell. I learned they even sing, fight, and socialize. All this with the energy consumption of 0.014 kcal across their entire lifetime. Sixty days of fruit fly behavior is equivalent to the 0.1 seconds energy expenditure of modern AI models - approximately the amount of text in this paragraph2.

AI models impress on task benchmarks, but energy demands per standardized tasks are rarely compared against biological baselines. AI workloads, as well as robotics could do a lot more for us if we knew how brains efficiently process information.

Insights harvested from organisms as small as the fruit fly have already changed the world. For decades, scientists have scouted a myriad of plant and animal for such discoveries. Instead of cumbersome lab work, piggy back on hundreds of millions of years of evolution and source them there.

Enzymes for cheap gene sequencing - discovered in a hot-spring bacterium.

Latest GLP-1 obesity drugs - extracted first from lizard venom.

Reusable adhesives - inspired by gecko toes.

The list is long.

And just how humanity scouted nature for molecules, we could mine “millions of years of general purpose algorithmic development”. Organisms had to tackle a vast landscape of computational problems in the past. Generation after generation had to get better at it.

—

Engineers all over the world rely on simulation software when constructing tools, buildings, or whole industrial facilities. In fact, the research shows that comprehensive simulation is a key factor to prevent cost overruns. Despite regulators’ encouragement, we often don’t have the same level of digital test abilities in biology.

I’m not arguing that brain emulation models will digitize the complete neurological drug-development process. To the extent that airplane simulations don’t replace windtunnel testing, brain emulation models won’t replace physical pharmacological experiments. But they could certainly significantly streamline and facilitate experimentation which neurons or brain areas to target in mental health interventions and diagnostics. And we might be able to tell what neuronal firing patterns cause life in misery or bliss. Mapping such insights to AI parameters might also be key to the nascent “AI Model Welfare” research area.

—

The most accurate brain emulation models raise profound questions about the relationship between physical brain states, consciousness and personal identity. Which is why technology optimists get excited and science fiction TV series upload humans into cyberspace. An exceptionally accurate brain emulation model could at least in theory include all the details about a given organism. Memories, personality, consciousness.

How much accuracy identity-preserving brain emulation models demand is absolutely unclear. But brain emulation models will most likely be the best available litmus test for we have for whether we understand memory, personality and consciousness.

—

While work on these objectives is not exclusive to brain emulation models, they are a strong candidate for transformative societal impact. If scientists could study brains on computers at sufficient scale, the world and our perspective on it likely changes substantially. If that resonates with you, the upcoming chapters provide the necessary context to participate in the conversation. And we need society to engage with and guide one of the most significant scientific efforts imaginable.

III. The State of Brain Emulation in 2025

Introducing existing brain emulation attempts and their underlying data collection methods. A novice-friendly summary of the State of Brain Emulation 2025 report.

| In Short: What is the State of Brain Emulation in 2025?

A small number of brain emulation models exists. These models combine wiring diagrams, basic cell types, simple neuron models, and virtual bodies. For worms, larval zebrafish, and fruit flies they cover the whole brain. Mammalian-scale models usually focus on smaller brain areas. No brain model should be considered fully biologically accurate yet. The storage and compute needs per neuron are open-ended. A digital neuron and its synapses usually need thousands of parameters. They take up between 1 and 100 KB each and need 1-10 million operations per second. This is comparable to the resource demands of dragging a small 64×64 pixels emoji on a power point slide with your mouse. A modern laptop can comfortably run insect-scale brains. For the mouse brain state-of-the-art GPU-clusters are required. Researchers tested a basic human-scale brain model on about 14,000 GPUs. Bottlenecked by the connection speed between GPUs, it ran at a 120 times slower pace than real time. Ideal neuron recording requires single-cell resolution, frame rates over 40Hz, and hour-long recordings. Maximum recordings achieved with single-cell resolution often are far below ideal frame rates or recording duration. Recordings cover ~0%, 1%, 2%, 50%, and ~80% of the total neurons for human, fruitfly, mouse, C. elegans, and larval zebrafish, respectively. Brain size and interspecies differences in neuron size and complexity explain most of the variation. R&D and equipment dominate costs. An hour of neural activity is thousands to tens of thousands of dollars. If trends continue, robust whole-brain recording for small insects may be achievable soon. For mice, it may not happen until late this century, if at all. To reconstruct neural wiring diagrams, scientists take 25-50 Megapixel tissue images. Each pixel represents about 15x15x15 nm³. They then align millions of picture tiles to form a 3D volume and use image recognition tools to trace neurons across tiles. Manual human proofreading of split and merge errors by neuron tracing algorithms is by far the most labor-intensive process. Scientists have completely mapped the brain wiring of eleven organisms: nine worms and two fruit fly. Some partial brain reconstructions are also available. Currently, the cost for end-to-end reconstruction per neuron is about $100 for sub-million-neuron organisms, >$1,000 for mice. There aren’t any molecularly annotated connectomes yet. However, thanks to advances in expansion microscopy, they could arrive soon. |

|---|

The Digital Zoo

Modern zoos can house thousands of species. The digital zoo of emulated organisms is still young. A decade ago, we had little to show. Now, a few exhibits give a real sense of early brain emulation models. All are still in development. Some are only available to those willing to invest time and money to instantiate them. The four biological counterparts all show diverse behavior patterns. And with more neurons, their range and idiosyncrasies become more impressive:

The microscopic nematode worm, C. elegans

Larval stage of the zebrafish

Adult fruit flies

Rodents like mice and rats

The respective brain emulation models use the best available neurobiological data. This generally includes:

Neuronal connections and basic cell types

Modeling of electric activity in neurons within biological limits

Some form of virtual body, allowing the brain to interact with the world

Figure: Neuron count of Model organisms in neuroscience.

|

|---|

Worm

The smallest organism of our digital zoo is the microscopic worm, C. elegans. At just one millimeter, it has a transparent body and is easy to modify genetically. This makes it a favorite in labs beyond neuroscience. With its 300-neuron nervous system, the worm explores its environment, shows basic learning and memory capabilities when it associates smells with experiences. Worms coordinate in groups during feeding when food is abundant.

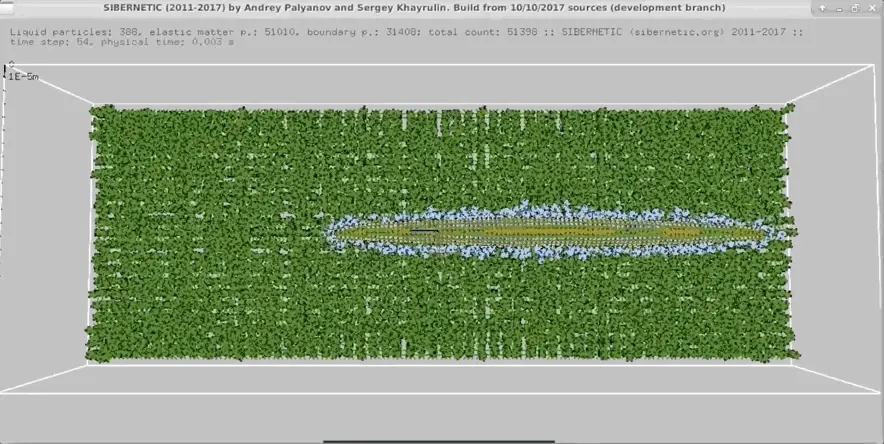

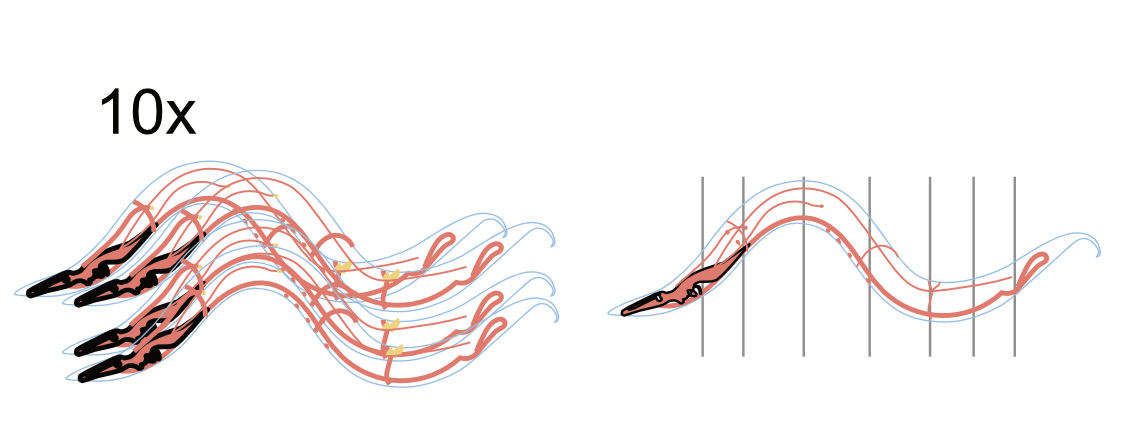

In the 2010s, the OpenWorm project built a first-of-its-kind multi-scale biophysical brain simulation. It integrated structural connectivity data with models of ion channels and body mechanics. You can see the results in the figure below. BAAIWorm is a newer implementation by chinese researchers that introduced a closed-loop model for locomotion. The resulting behavior repertoire remains limited and often inaccurate. But both are remarkable achievements given the comparatively limited funding available for this work.

Larval Zebrafish

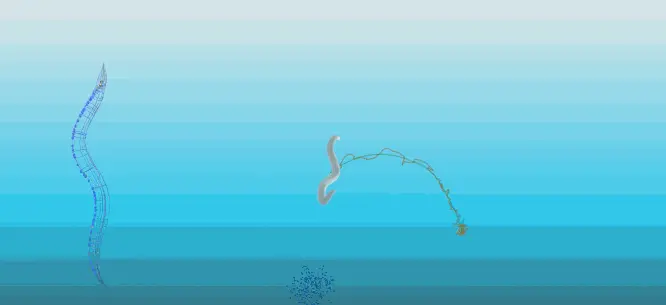

During the first 30 days after fertilization, zebrafish share many of the research tractability advantages of C. elegans. Their transparent larval bodies make it easier to study the activity of about 100,000 neurons. In addition, Zebrafish neurons have action potentials that are similar to those in humans. The larvae show behaviours such as prey hunting, escape responses, response to light. (see videos below) They also learn from past experiences.

Liu et al. (2024) developed simZFish, a brain model focusing on the visual-motor response. It combines a simple neuron network with biomechanics and a virtual visual system. As the only organism in our digital zoo, we can see a robot that swims in water (see figure below). The Zebrafish also is unique in that a comprehensive Benchmark was recently released. The Zebrafish Activity Prediction Benchmark (ZAPBench) is a first of its kind forecasting challenge to predict future neural activity from past observations for over 70,000 neurons recorded during behavioral tasks. Lueckmann et al. (2025) tested first approaches, including time-series models and volumetric video predictions. Once the ongoing neuron wiring diagram reconstruction is complete, this will be one of the most promising aligned datasets available for further brain modelling.

Fruit fly

The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, walks and flies with rapid maneuvers. It shows behaviors like grooming sequences and aggression. Complex courtship rituals involve species-specific songs, learning, memory, and even idiosyncratic "personalities". I highly recommend taking a look at the videos on fly behavior below to get a better sense of the impressive behavior repertoire.

Shiu et al. (2024) used this data and modeled over 127,000 neurons. They then successfully validated the model against known feeding and grooming circuits in real flies. An independent effort is the detailed biomechanical model called NeuroMechFly. It is a functional virtual body that is planned to be connected to neurons eventually. NeuroMechFly’s walking, grooming, and visually guided flight result from a blend of bio-inspired control methods.

Rodents

People who spend time with rodents appreciate their rich behaviors and unique personalities. Mice, with ~70 million neurons, have brains with about ~500 times more neurons than those of fruit flies. Rats have roughly 3 times more neurons than mice.

In 2020, Billeh et al., 2020 modelled a fraction of the mouse visual cortex containing ~52,000 neurons. Connection parameters were inferred from various physiological datasets, and optimised to produce firing dynamics that matched in vivo recordings. The Blue Brain Project mentioned in the preface published partial brain models of rats (e.g., 4.2 million neurons, equivalent <10%). The largest imaged brain sample in rodents is only about 1 mm³. Thus, rodent brain emulation models have to use assumptions about neuron connections. No brain-controlled biomechanical rodent models exist yet.

And that's our digital zoo. The videos below compare real organisms' behavior with their digital replicas. In our SOBE-25 Report, we describe additional computational brain emulation models. I selected the ones here for their strong illustrative value.

Video of C. elegans behavior C. elegans responding to a touch stimulus |

Figure of OpenWorm simulation: Demonstration of a computational model of the worm C. elegans. (Github page, 2024)

Replication from Figure BAAIWorm moving towards simulated chemicals. Video showing the simulated worm (ref)

|

|---|---|

Videos of Fruit fly Behavior Fighting A male fruit fly is courting a female fruit fly. Social mating behavior |

Shiu et al fruit fly emulation https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZVoPJumx8Y&t=66s NeuroMechFly is a virtual body for the fruit fly that is planned to be connected to a neuron model eventually. GitHub Repository |

Videos of Larval Zebrafish Behavior |

Lueckmann et al. 2025; from Google Blog. Side by side comparison of a brain activity map. Left: Ground truth. Right: Prediction. Due to copyright restrictions, we can’t replicate the simZFish video here, but you should absolutely check it out on bioRxiv! They even tested it as a robotic fish swimming in water. |

Videos of rodent behavior |

[no visualizations of mouse brain emulation with virtual bodies exist yet ] |

Human

The state-of-the-art human modelling attempt is a brain emulation model by and of Prof. Jianfeng Feng. The mathematician at Fudan University in China was not the first to build large human brain models. Japanese researchers simulated the 68 billion neurons in the cerebellum in 2021 and other preliminary models.

But Feng et al were the first to push all the way up to simulating all 86 billion neurons3. Prof. Feng’s MRI brain scan guided the connectivity and density of neurons. Despite a dedicated engineering team and access to a 14,012 GPU supercomputer, the model ran about 10h to replicate 5min of biological clock time, a 120 x slowdown. This is a testament to speed bottlenecks moving data across devices we will discuss in a bit.

The team then went further and performed plausibility checks on the brain model against its biological counterpart. Since the model produced neural spikes, they implemented a "neural spike to fMRI signal" converter. This way they were able to compare Prof. Fengs fMRIs with predicted fMRI signals. They found moderate correlation signals. With a model so large and test data so small, this was not particularly surprising. Nonetheless, this work is a significant proof of concept and at the very frontier of computational challenges in emulating human brains.

–

Watching organisms move on a screen or viewing predicted fMRI correlations is remarkable. But movements are slow, simplified, and often repetitive. Digital behavior doesn’t last long and lacks the depth of real organisms. It’s like being welcomed to the world's most disappointing zoo - where even the worm can't really crawl.

Right now separating the digital from biological counterpart is trivial. Which brings us to the behavioral evaluation axis we gestured at in the first chapter. But instead of a list of criteria, I want to introduce a slightly more elegant concept: All brain models today fail the so-called “embodied” Turing test - an analogy to the famous Turing test for AI. The original version states that if you can’t tell a human from a computer in a blind chat, it’s AI. In neuroscience, the above authors suggested an adaptation. The challenge is to distinguish the digital from biological behavior. Once a brain emulation's virtual body behaves just as a recording of a real organism, you pass4.

Neuroscientists will confirm that the neuron models also differ from biological ones. It's less dynamic, less diverse, and can spiral into chaos without intervention. Our current brain emulation models are not yet biologically faithful.

The main factor driving complexity in brain emulation models is the detail per neuron. This is measured by the number of parameters. Parameters aren’t much more than a number in a very long mathematical equation to account for neuronal firing speeds, delays and recovery periods, and synapses. The more parameters, the richer the repertoire of a digital neuron. Simple models consider neurons as points with connections to other neurons. More detailed models distinguish neuron subcompartments and synaptic idiosyncrasies. This improved accuracy increases the aforementioned parameter count easily by 100 times or more.5

Figure from Introduction to Neuroinformatics Summary, Camenisch

|

|---|

A single neuron can easily have 50,000 free parameters. To put this into perspective, a fruit fly parameterized with neurons at this accuracy is like a 2019 LLM6. For humans, this would amount to 1,000 times more parameters than the latest generation LLMs.7

And as parameter counts grow, so does the challenge of configuring them. Adjusting parameters to fit experimental data is called "model fitting." In its simplest form, this involves manually setting shared parameters based on experimental data. The more parameters, the higher the accuracy - if data is available8. This way, models can account for ion channel densities, membrane properties, or synaptic strengths. Researchers then have to turn to machine learning for fitting massive parameter counts. The number of parameters often exceeds what guidance data can provide, i.e., we can't accurately determine the parameters or get multiple incompatible solutions.

More parameters are also more demanding for hardware. Parameters must be stored in memory and used many times per second for computations (FLOPs). If one device lacks enough storage, processing units need to communicate (interconnect speed)9. This is exactly what happened with the full scale human brain model we just talked about.

The conclusion of this chapter: great neuron models need a lot of parameters. To be useful, these in turn require a lot of data. We’ll look next at how neuroscience collects high-quality datasets.

Computational Neuroscience: Uses mathematical models, brain data and simulations to understand how the brain processes information. (Digital) Neuron Model: A mathematical or computational representation of how a neuron behaves. It ranges from simple point-like units with connections to detailed simulations that include ion channels, membrane properties, and structural compartments. Parameters: Numbers that define a neuron model's properties (like ion channel densities or connection strengths); more parameters enable greater biological accuracy but require more data and computing power Virtual body: A simulated physical body (including muscles, joints, and sensory systems) that allows a brain emulation to interact with a digital environment, enabling behaviors like movement and response to stimuli GPU (Graphics Processing Unit): A specialized computer chip originally designed for rendering graphics but now widely used for parallel computation in scientific modeling and AI FLOP/s (Floating Point Operations per Second): A measure of computational speed indicating how many mathematical calculations a computer can perform each second Tera, Peta, Exa (prefix): one trillion (10¹²), one quadrillion (10¹⁵), and one quintillion (10¹⁸) |

|---|

Neural Dynamics

Today’s smartphone cameras often capture videos that look like real life. Neuroscience hasn’t reached this level yet. Even the best neural recording equipment struggles. Recordings are either low resolution or show just tiny parts of the whole image. They tend to be brief and choppy, revealing only contours and edges. Very limited colors. Even the slightest movements while recording can cause issues.

Accuracy in neural recordings involves several factors:

Single-neuron resolution lets us observe neurons firing.

Very high frame rates (Hz) allow us to track events happening many times per second.

Labeling structures, including neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, and hormones.

Natural behavior means the data reflects the brain doing real work, not just resting.

Long durations help us capture patterns over time.

Large volumes aim to record as many neurons as possible, ideally across the whole brain.10

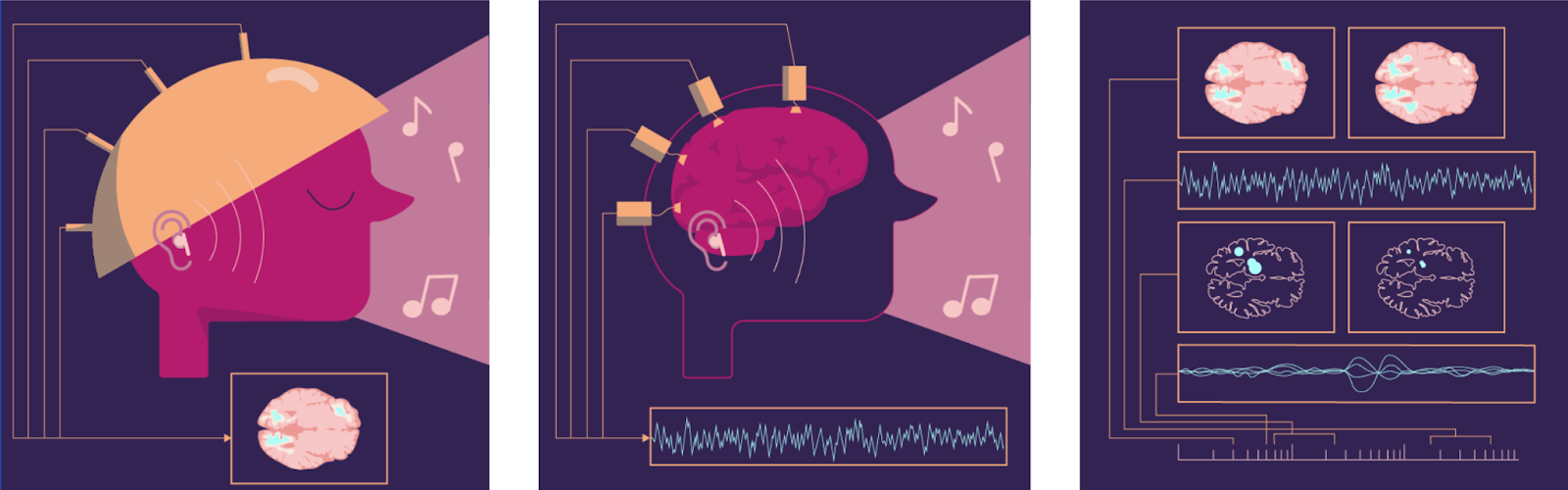

The figure compares coverage, resolution, speed, and duration in key recording methods.

Whole Brain Recording: The measurement of neural activity across an entire brain of an organism. We define it at at least ≥ 90% of all neurons in the brain of a given organism. Single-neuron (single-cell) resolution: The ability of a recording modality to isolate signals from individual neurons rather than aggregates. Practically, this requires sufficient resolution and signal-to-noise to assign activity to distinct cells. Temporal resolution / frame rate: The number of measurements captured per second (measured in Hz); higher frame rates (e.g., 200 Hz) can track rapid neural events like action potentials, while lower rates (e.g., 1 Hz) may miss fast dynamics |

|---|

Figure: Comparison of different recording modalities Comparison across four dimensions. Resolution as number of individual cells recorded. Speed as temporal resolution in frames per second. Maximum recording duration per session and total volume recorded. An ideal recording method for whole-brain human recording would rank at the top of each bar.

|

|---|

Non-invasive methods like EEG and fMRI capture electrical activity across human brains. Doing so, they sacrifice resolution. EEG measures voltage changes across large superficial brain areas with millisecond precision. But this aggregates signals from millions of neurons.

fMRI has decent spatial resolution of about 1 mm³ across the entire brain. It measures blood oxygen which is correlated with neural activity. This averages tens of thousands of neurons11 over 1-3 seconds. It may not sound dramatic, but it is. This compression is similar to shrinking a modern 4k smartphone video down to a single pixel12. Plus, it’s greyscale and flickers every two seconds, rather than changing smoothly at 60-120 frames per second (Hz).

Functional ultrasound (fUS) is an invasive method that works best with a probe in the skull. Similar to fMRI it tracks blood oxygen. Resolutions are 0.004 mm³ (100x100x400 μm³) and sampling rates 100 times higher than fMRI. In the smartphone analogy the 4k 7000x7000 pixel video is now compressed to 15x15 pixels. Still not very informative, but it runs smoothly at 120 Hz. With centimeter-scale fields of view, we only cover small parts of the human brain though.

Note that none of the methods mentioned so far are capable of single neuron recording. There are two central single-neuron recording methods, both of which are invasive. They are limited to microscopic brain areas, about a millimeter wide. Additionally, they carry surgical risks and can restrict natural behavior. Microelectrode arrays (MEAs) are small implanted chips with electrodes to record from tissue. Implanting them inevitably causes microlesions, even for superficial brain regions. At arbitrary sampling rates and recording durations, they capture up to thousands of neurons

In contrast, optical microscopy techniques detect activations in neurons visually. Fluorescence indicators light up when an action potential is propagated by a neuron. These indicators have to be genetically encoded. Special microscopes are required that at incredible speeds change between planes of tissue and thereby create a whole stack of pictures that reconstruct to a volume. At a resolution of 1x1x15 = 15 µm³ (or 0.000000015 mm³) per pixel, fluorescence imaging can identify hundreds of thousands of individual neurons in mice. For other organism resolutions can be 1 µm³ or less and neuron counts much lower13. Calcium imaging has sampling rates of 1 to 30 Hz; voltage imaging up to 200 Hz, but for smaller volumes.

With single cell resolution, the smartphone video is now finally in full resolution. But, alas, we are far from recording the whole brain at once. fMRI was helpful insofar it recorded from the whole brain at once. With single cell recordings the largest volume we can record is equivalent to single digit datapoints of fMRI, i.e., a few mm³. Usually recording durations are broken into bursts of seconds to minutes as indicators need to recover and we get a total of a few hours in total.

Understanding how far we are from single-neuron recording in mammals can be hard to grasp. Here’s are two illustrations to help: First, if a single mm3 is a 4k video on your smartphone, scaling to a whole-mouse brain, one frame comes at 30 billion points or 30,000 Megapixels, comparable to some of the largest continuous images of whole cities. Second, see the following figure that compares volume and resolution of different modalities. Fluorescence microscopy is sharp down to a single plane, whereas functional Ultrasound or fMRI are crude pixels, even at the level of a whole cubic millimeter. But on the flipside fluorescence imaging can only cover a fraction of the mouse or human brain, whereas functional ultrasound can at least in theory cover the whole mouse brain and fMRI the whole human brain.

Figure: Comparison of volume and resolution of recording modalities. Resolution and volume comparisons for different modalities. Voxels per volume are calculated at a given resolution and represented in 2D. Resolutions are 15 µm³, 0.004 mm³, and 1 mm³ for calcium imaging, fUS, and fMRI, respectively. Equivalents for a map at 1m²/px resolution would be Manhattan for the insect brain, the whole state of Massachusetts for Mouse and the entire world for human brain scale. Data; source images 1, 2, 3.

|

|---|

All this to say: there isn't an "optimal neural tissue recording" that captures all biological dimensions. Even in sizes smaller than a cubic millimeter we run in tradeoffs. Some studies on worms, fruit flies, and zebrafish mention “single cell whole-brain” recording. However, none reach even the expected coverage implied. For the SoBE-25 Report, we found no publication that truly recorded all brain neurons at single-neuron resolution in any organism. In addition, these whole-brain recordings lack high frame rates and long recording durations.

In C. elegans, the best recordings capture about 150 head neurons. That's roughly 50% of the nervous system. Across 284 worms this amounts to around 10s of hours of single-neuron recording, mostly at 10Hz or slower.

In zebrafish, advanced techniques record ~70-80% of neurons at ~1 Hz [Ahrens et al., 2013, Lueckmann et al., 2025]. Recordings often require immobilised animals due to motion artifacts. Newer methods aim to adapt to freely moving larvae [Chai et al., 2024].

In fruit flies, Schaffer et al. used swept confocally-aligned planar excitation (SCAPE) microscopy to image the dorsal third of the Drosophila brain (450 × 340 × 150 μm³, ~57%) at single-cell resolution at 8-12 Hz, though scattering makes resolving individual neurons in deeper brain structures difficult (Schaffer et al., 2023). This amounted to approximately 1,500 neurons being imaged.

[Schaffer et al., 2023] recorded up to ~1,500 cells at 8-12 Hz in the central brain of the fly, i.e. about 1% of all neurons. The particular challenge with the fruitfly is that neurons in the optic lobes are extremely densely packed. While whole-brain imaging can be performed, it currently doesn’t resolve at single-cell resolution. For instance Gauthey et al. recently demonstrated near whole-brain imaging (e.g., encompassing the central brain and optic lobes) at 28 Hz in preparations (Gauthey et al., 2025). Individual voxels were ~10 times larger than necessary for reliable single-cell resolution.

In mice, the percentages drop significantly. Only 1–2% of neurons have been recorded in parallel. The MICrONS consortium imaged activity of ~75,000 neurons at 6–10 Hz for ~2 hours [MICrONS Consortium, 2024]. Newer methods have imaged up to 1 million neurons [Manley et al., 2024] at similar speeds. The International Brain Laboratory and Allen Institute, recorded neurons during complex tasks. Thanks to MEAs like the Neuropixel, recordings had a high temporal resolution, but were limited in count to few hundred neurons per neuropixel probe.

In humans, single-cell recordings usually involve hundreds of neurons. This rounds down to 0% of the total brain volume. Ethical and technical limits restrict using genetic tools, like calcium indicators. So, we depend on implanted chips / MEAs instead. Neuralink’s N1 implant has 1,024 electrodes. That gets us to about ~300–1,200 neurons via spike sorting.

Most papers report the number of neurons and their recording speeds. Plotting the results from past studies shows a solid track record (see figure below). But this trendline shows that whole mouse brain recordings at high recording speeds is decades away. We can either wait a long time, stay very hopeful about tech progress, or find creative solutions to bridge to larger brains.

Structural brain data of whole organisms could provide such a bridge. We’ll discuss details in Chapter Three. First, we need to understand the challenges of reconstructing brain wiring diagrams: connectomes.

Figure: Estimated instantaneous information rate of neural recordings over time. This metric counts the number of neurons recorded at once. It multiplies that by their effective temporal resolution, limited to 200 Hz. We distinguish optical imaging including methods like calcium imaging and electrophysiology. Horizontal dashed lines indicate theoretical maximum information rates for selected nervous systems.

|

|---|

Connectomics

Earth’s surface area is about 510 million square kilometres. If we image our planet at 1m² per pixel, the file size would be 1.5 Petabytes, or 1,500 terabytes14. Keep that in mind for later.

Even fluorescent microscopy resolution is not enough to accurately map the connections between neurons. For that we need to be able ot look at the smallest neuron structures, not just the neuron’s bodies. Synapses are only a few hundred nanometers wide. The gaps between them are just 20 to 30 nanometers. The finest nerve fibers are tens of nanometers in diameter. Accordingly, a single scanned voxel (3D pixels) must resolve 10-20 nanometers in each direction15. One 15 µm3 voxel in our neural activity recordings turns into 2-15 Million points with such “ultrahigh-resolution” scanning.

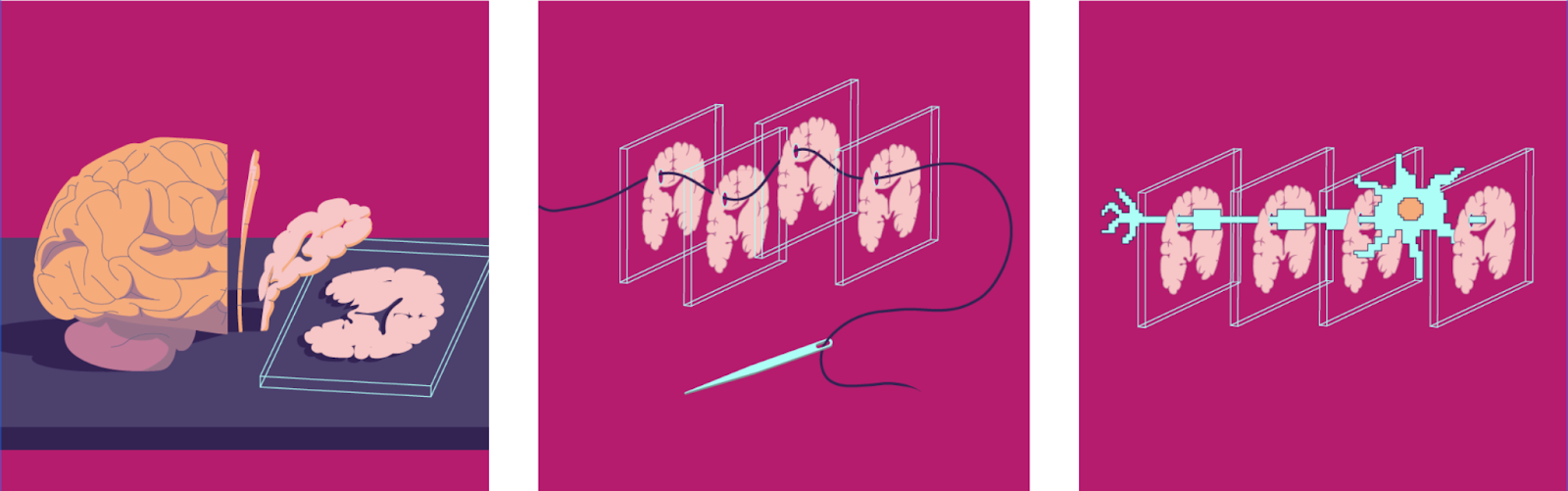

For decades, electron microscopy (EM) was the only method for nanometer-resolution brain images. Modern electron microscopes easily reach resolutions of about 10x10x10 nm³. However, this process is slow and often destructive. It involves staining, ultra-thin slice cutting, expensive grid tape films, and more. A report from the Wellcome Trust estimates that 20 electron microscopes running 24/7 for five years could scan a mouse brain16.

Scanning liters of human brain volume slice by slice at this resolution is a different challenge. It would create a staggering file size of about one zettabyte, or one billion terabytes17. Humanity’s total data storage capacity in the year 2025 is estimated at around 10s to 100s of zettabytes. Even with 2x lossless compression, a single human brain map would still need a small percentage of all human digital storage capacity.18 The map of our brain is about one thousand times larger than the above mentioned map of earth.

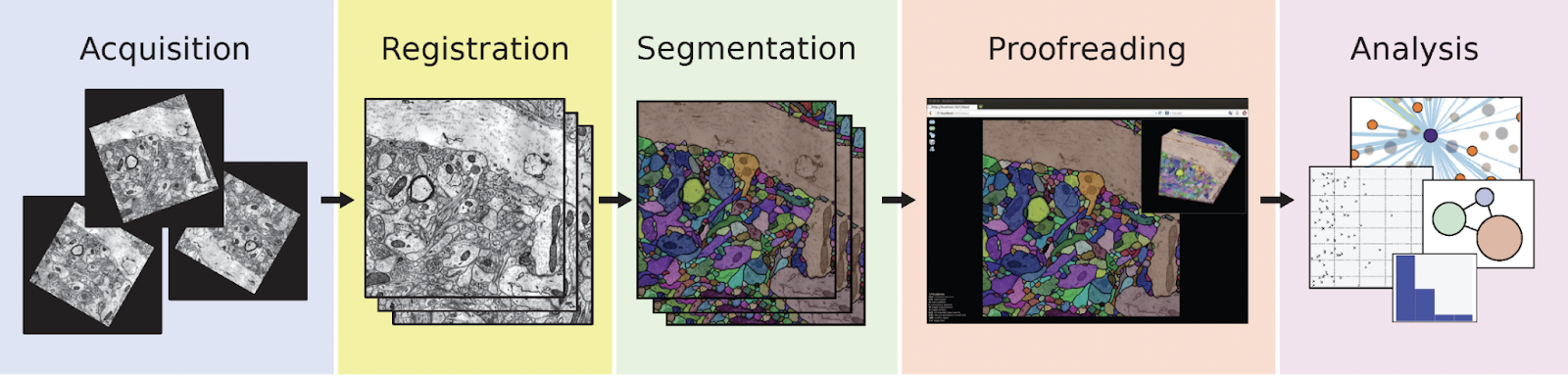

This is one of the many reasons why scanning the human brain is an incredible challenging undertaking. Raw image data needs to be processed into a graph of neurons and their connections19. This task is actually a bigger challenge than "just" scanning and storing lots of data. Image tiles need to be realigned into volumes. Neurons traced through them. Outputs validated. In the 1970s and 1980s, White et al. literally spent a decade manually processing data for a single millimeter sized worm with ~300 neurons. After a long pause the field finally saw big improvements in the 2010s. Acceleration happened thanks to advances in processing speed and image recognition algorithms. Still, processing a mouse brain scan with 1,000 GPUs would have taken 226 years in 2022. Newer algorithms and improved GPU capabilities have compressed this to 1-2 years today.

But even modern algorithms are not perfect. They still make "split" and “merge” errors (breaking or joining neurons). Correcting these requires human proofreading. For example, it takes around 20 to 30 minutes to proofread a single fruit fly neuron. A single complex mouse neuron can easily take 40 hours or more. Thus, proofreading costs and time dwarf sample preparation, imaging, and processing easily by 50 times.

Figure Connectomics pipeline. A) From Mineault et al, 2024, for a complete pipeline overview. B) Stages of image processing compared to raw satellite data. Registration (left), segmentation and tracing (centre), and annotation and analysis (right). Source: Schlegel, 2024 A)

B)

|

|---|

Scientists have created complete brain wiring diagrams for about 10 individual organisms. This includes one female and one male fruit fly and several worms in different stages of development. In October 2024, the first complete wiring diagram of the ~140.000 neurons in a female fly’s brain was published (ref). In late 2025, we got the the male counterpart, that also includes the fly’s “spinal cord” (ref). Other efforts have reconstructed parts of the brain or are still proofreading. Overall, whole brains or small parts of brains from about 20 organisms have been scanned in meaningful volume worldwide.

Connectome: A complete wiring diagram showing all neurons in a brain and how they connect to each other through synapses Synapse: The tiny junction (20-30 nanometers) where two neurons connect and communicate, allowing signals to pass from one neuron to another. Voxel: A three-dimensional pixel representing the smallest unit of volume in brain imaging; voxel size determines the spatial resolution (e.g., 10×10×10 nm³ for electron microscopy vs. 1×1×1 mm³ for fMRI) Reconstructed neuron: A neuron that has been fully traced through brain imaging data, had all its connections (synapses) identified, and undergone human proofreading to correct algorithmic errors Proofreading: The manual process of correcting errors made by automated neuron tracing algorithms, particularly "split" errors (incorrectly breaking a neuron apart) and "merge" errors (incorrectly joining separate neurons together). |

|---|

Table: Synaptic resolution Electron microscopy brain wiring reconstructions - Overview of brain wiring (connectome) reconstructions in four model organisms. Blue: scanned. Red: scanned and traced.

|

In 1986, White and colleagues published the first complete wiring map of the C. elegans. This marked the first fully described connectome. Subsequent efforts added different developmental stages and the male nervous system. “Original” composite C. elegans connectome. (EM). Synaptic resolution. (White et al, 1986) C. elegans: 10 complete connectomes and one composite. This includes both sexes and five different developmental stages (EM). (Varshney et al., 2011, Cook et al., 2019, Brittin et al., 2020, Witvliet et al., 2021) |

|---|---|

|

Zebrafish at roughly day 5: Various datasets from different individuals exist

|

As you can see, this is a very active field of research. The mind of a mouse, was the title of a 2020 position paper to argue that a mouse connectome might be feasible. Today, this seems even more possible with new microscopy methods and improved algorithms. In 2023 the NIH launched an effort to scan about 1/30th of a mouse brain by 2028 and build infrastructure for a complete connectome by 2033.

Connectome reconstructions work well on the cubic millimeter scale, which neatly aligns with what neural recording methods are capable of as discussed in the chapter. For larger brains, experts in connectomics point to two main concerns.

First, costs, especially from proofreading. The costs per neuron fell from ~$16,500 for C. elegans in the 1980s, to ~$214 for the Drosophila and ~$100 for zebrafish larvae as of 2025 . Larger animals, however, often have more complex neurons. For rodent neurons the average price is often still about $1,000 per neuron. But even at the ~100$ per neuron pricing, the total cost of a mouse connectome remains in the range of $7-21 billion, as per Wellcome Trust report. This puts three orders of magnitude larger human connectomes are out of reach.

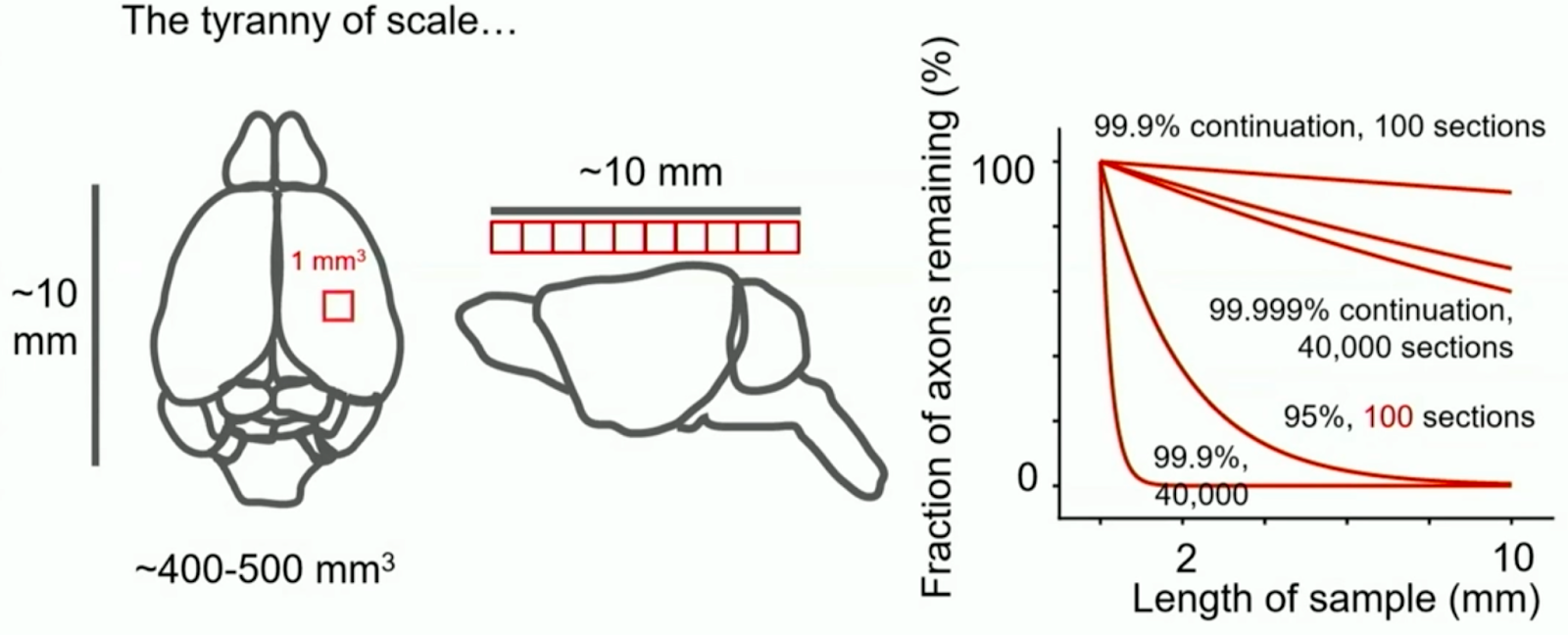

Second the "tyranny of scale" from billions of image tiles. Even minimal error rates can add up over large volumes. A 0.001% neuron tracing error rate across tiles sounds robust. In larger brains, neurons can reach several millimeters or centimeters. Accordingly, when sliced at nanometer resolution, even small error rates amount to many errors per neuron.

Fortunately, some of the sharpest minds conceived solutions. From the tyranny of scale to proofreading costs and single-cell neural recording limits, ideas exist.

Figure: Replication of the Tyranny of Scale - Figure from the NIH Brain Connects Workshop Series. Even at low error rates, tracing accuracy declines with many imaging sections in large brain volumes

|

|---|

IV. Gaps in making brain emulation models a reality

| In Short: Gaps to Brain Emulation Models.

The staff count of neuroscience organism consortia is less than 5% of that of a single flagship project, like the Human Genome Project. Eventually large-scale brain data acquisition will necessitate industrialized "brain fabs". This would come with a shift from academic groups to centralized organizations. Advanced automated neuron tracing promises to reduce proofreading costs by 50 to 100 times in the coming years. Then imaging and storage will become relevant cost drivers of neuron reconstruction too. Expansion-based light microscopy could bring the ability to label molecules. This way a given image captures richer information about the tissue. Further, this capability allows to label cells with unique sequences. The process called barcoding effectively removes the need for proofreading. Structure-to-function machine learning methods could help overcome the limits of current single-cell recording methods. AI models might learn to derive neural activity from static brain images. Training happens on datasets pairing single-cell neuronal activity, nanometer-scale images, and molecular annotations. The goal is to infer one from the other, equivalent to training of voice-to-text models. This approach remains speculative and unproven. |

|---|

The last chapter might suggest that all brain emulation challenges are technical. While these are genuine challenges, technology isn’t the only limiting factor. We want to discuss four key gaps:

Professionalization Gaps: What improves effectiveness and efficiency?

Connectomics Gap: How can we reduce connectome costs?

Recording Gap: What allows recordings from mammalian-sized brains?

Non-Neuron Gap: Variables like Neuromodulators, Glial cells, hormones and vasculature.

Closing the Professionalization Gap: Centralization, Industrialization

The Human Genome Project engaged thousands of scientists from over 20 institutions worldwide. CERN has 2500 staff members and collaborates with over 12,000 scientists globally. The James Webb Telescope involved over 10,000 people. Each of these projects cost around $10 billion.

After a decade, OpenWorm lists about 125 people on their contributors site. From conversations with larval Zebrafish researchers, we know that the number is much smaller for their domain. The Microns consortium lists about 100 names. Last year’s fruit fly connectome paper acknowledges about 300 members of the Flywire consortium.

Steven Larson, who used to lead the OpenWorm project, spoke about the challenges of emulating the worm in a 2021 interview. OpenWorm relied on data from other scientists and couldn't opine what data to gather next. Individual components of the brain emulation pipeline were isolated.

Brain emulation is highly interdisciplinary. Recording from living, scanning fixated brains, computational modelling are distinct artisanal crafts. Labs often excel in specific methods. Working in cross institution collaborations is not an ideal fit for such an extensive pipeline. It takes way more time and unrelated projects often bring distractions.

These challenges in the brain emulation ecosystem seemed to have been influential in conceiving a completely new type of organization - Focused Research Organizations (FROs). Focused stands for the pursuit of “prespecified, quantifiable technical milestones rather than open-ended, blue-sky research”. Spearheaded by the non-profit Convergent Research, these organizations try to resolve key scientific bottlenecks that stay unaddressed by academia, startups, or large corporations.

FROs aim at a staff count of 10-30 individuals and funding over approximately 5 years. Larson proposed an even larger centralized institute. Well-resourced, it would attract top talent in neuroscience, engineering, and AI. This idea isn’t new. He compared it to research campuses like the Allen Institute or Janelia. While work there is synchronized, there is still a lot of independence. Not everything is focused on a shared mission.

A central entity could unify experts and set a common goal. Like creating the first biologically faithful brain emulation model. And then build scalable infrastructure that is otherwise too costly.

The semiconductor industry already processes materials with multiple electron microscopes in each facility. Biotech facilities routinely screen and store millions of samples with microliter precision. Diagnostics firms manage over 100,000 tests daily with automated workflows. CERN’s data centers handle exabytes of scientific data at bandwidths over 100 GB/s.

Such capabilities could be merged into a central brain emulation facility - a brain fab. A place dedicated to scaling the brain emulation pipeline to the demands of faithful brain emulation models (see figure). Instead of separating them, it would bring recording, scanning, processing and modeling all to one location. This maximizes automation, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency. And it could create hundreds, if not thousands, of high-tech jobs - returns to society similar to what we previously outlined for other large-scale science investments.

Figure: Brain Fab Visualization. a 3D visualization of a purpose-built facility for brain emulation. It covers recording, scanning, processing, storage and modelling. A prototype facility can be scaled up later to greater capacity. For comparison modern facilities like TSMC’s Arizona plant.

|

|---|

Closing the Connectomics Gap: Disrupting Costs per Neuron

We ended the connectomics chapter with a mouse brain connectome estimate of about $10 billion. This estimate was based on the current electron microscopy and human proofreading approach. It has been laid out in detail in the excellent 2023 Wellcome Trust report on connectomics.

Experts believe that the basis for this estimate has already changed and will further. With enough training data, machine-learning approaches almost certainly soon massively decrease human proofreading. The Fruit fly was about 33 person years of proofreading. The Wellcome Report estimated the human labor component for a mouse connectome on the order of 100,000 person-years. This corresponds to about 800 μm3/h. Results of a recent Google paper imply a 67,200 μm3/h. This translates to an 84x improvement in proofreading throughput. Depending on the hourly wages, a 50-100x improvement in proofreading brings down cost to the same level as imaging and storage. A 500x improvement, and it matches the speed of the second slowest step, imaging.

Imaging is experiencing a similar trend. Electron microscopy setups are getting cheaper over time. A recent publication used refurbished devices and achieved similar speeds at a 10th of the price of new ones.

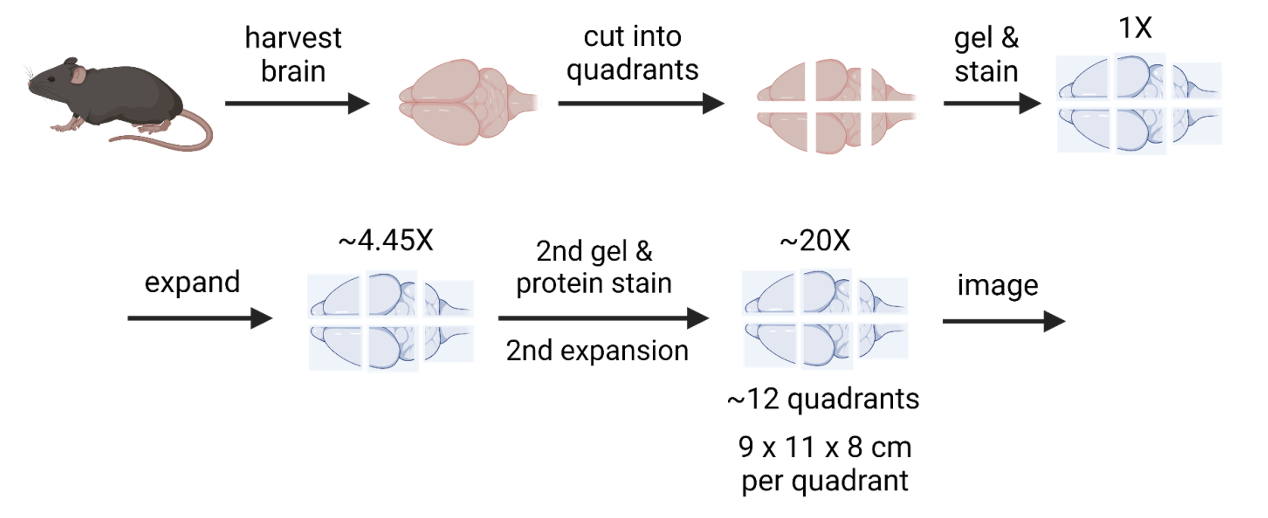

Expansion Microscopy (ExM) is a completely new approach. It involves embedding tissue in a swellable hydrogel, expanding it iteratively up to 20 to 40 times its original size. This allows effective electron microscopy resolution with usually more affordable light microscopes20. At comparable scanning speeds, this results in cheaper and / or faster image acquisition21. However, even expansion microscopy cannot eliminate the scale challenges of imaging a human brain. 24x expansion of a human brain is about 18 m3, 30–40 standard household fridges. Weighing on the order of 19 metric tons.

Figure: Expansion Microscopy Process - Illustration of the stepwise processing of brain tissue in the context of expansion microscopy. Credits to Eon Systems PBC.

|

|---|

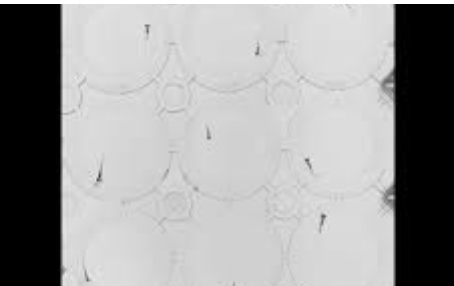

Even more importantly, ExM allows for antibody labeling. Researchers can tag molecules of interest in tissue scans with fluorescent proteins. This provides otherwise inaccessible information to later modeling stages. The benefit of having 10, 50 or 100 important proteins labeled are likely massive. Previously invisible features of neurons and synapses can be visualized. Having labels on top of morphology is akin to seeing the world with color patches instead of edges only (see figure).

Molecular Annotation: The process of identifying and labeling specific molecules (like neurotransmitters, receptors, or proteins) within neural tissue, providing chemical context beyond just structural connectivity Expansion Microscopy (ExM): A technique that physically expands brain tissue (like a hydrogel) before imaging, making nanometer-scale structures visible with conventional light microscopes—potentially cheaper than electron microscopy Barcoding (Molecular): A technique where each neuron is genetically labeled with a unique combination of proteins that can be read out through sequential imaging, eliminating the need for tracing neurons across images or human proofreading |

|---|

Figure: Molecular Labeling of essential proteins. Picture analogy to molecular labeling in connectomics. “Edges only” is what electron microscopy delivers us today. Demonstration of how more labels help reconstruct information. Five hundred 4x4 pixel features were extracted from the original image. This number is equivalent to a reasonable upper bound of molecules relevant for brain emulation models. The actual number of relevant molecules is unknown. Stages plot the top features increasing percentages. Full image.

|

|---|

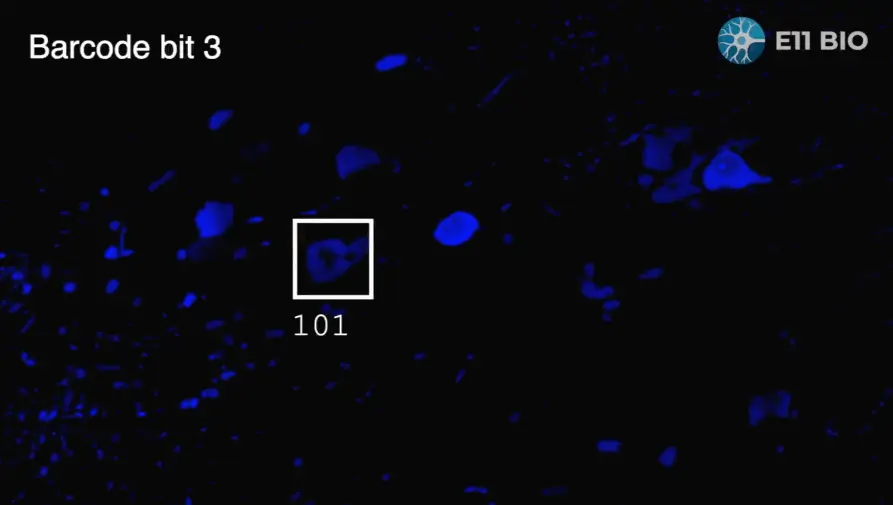

This molecular labeling capability can also be leveraged into a technique called barcoding. The Focused Research Organization, E11 Bio, is pioneering this effort. They first genetically engineer a random combination of 20 proteins into each neuron. Then they use sequential antibody labelling with fluorescent proteins to read out these "barcodes". Once you can read unique molecular signatures across entire neurons, no tracing or proofreading is required. Errors are easy to fix by re-checking the neuron for its barcode. Also, the needs for resolution, storage, and processing are much lower.

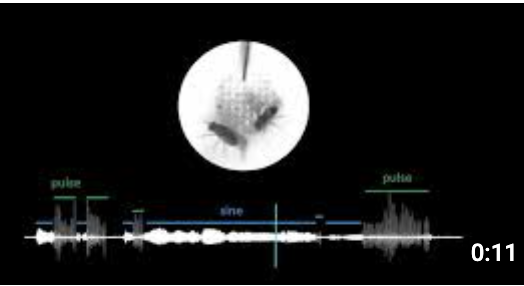

Figure: Barcoding. E11 demonstrates how molecular annotation can be used for barcoding neurons in expansion microscopy.

|

|---|

While writing the report we created a budget template to clarify costs in connectomics for ourselves. The following table shows the results for different paradigms for costs and timelines. We fixed many variables, so they are genuinely comparable. The table also includes a replication of the Wellcome Trust estimates. You can play around with numbers yourself here.

If a world with "minimal" proofreading comes true, mouse brain connectomes costs could fall below $50M. This assumes a multiyear project returning multiple connectomes. This way high upfront infrastructure expenditures ($150-250M22) and marginal acquisition cost ($30-90M) are averaged out.

As backup, barcoding could eliminate proofreading costs altogether. Either way would lead to a remarkable ~100x improvement over today’s costs. We plotted the results for $ per neuron below. This helps us see how future results with about 1$ / neuron stack up against previous connectomics projects.

At 0.1$ per neuron, a human connectome will approach the costs of past megaprojects. Proofreading seemed insurmountable, motivating entirely different ways to sidestep it. But it increasingly looks like it will be solved in time. The same might apply to other problems that seem insurmountable today. Let’s take this optimism and the significant cost savings in connectomics to discuss applying AI to neural recording challenges.

Table: Central estimates for the mouse connectome across different modalities.

Estimates are based on a 5-year project, 500mm³, 70 million neurons, $50M for microscopes, on-premises storage pricing, current compression ratios, backup and archive storage, fixed budget of 1,000 H100 GPUs, proofreading costs as provided, and fixed employment costs of $150,000.

Figure: Cost per Quality-Controlled Reconstructed Neuron This plot shows estimated inflation-adjusted reconstruction costs for major connectomics projects over the past 40 years. It includes current expert estimates and projections based on our budget estimates (plot, data).

|

|---|

Closing the Recording Gap: The Structure-to-Function Hypothesis for Large Brain Volumes

Based on current trends, whole-mouse brain scale recordings are decades away. For Human-scale recordings centuries, if not impossible. Accordingly, innovative ways to parameterize and fit neurons are necessary, when whole-brain recordings data is lacking.

Tissue scanning scales much better than in-vivo recording. So what if we had a complete wiring map of the brain, potentially with rich molecular annotations and aligned neural activity sub-samples? Could we train algorithms to predict activity in unmeasured areas? This brings us to the structure-to-function hypothesis.

Aligned Dataset: A dataset pairing multiple data types from the same brain tissue (e.g., neural activity recordings matched with the connectome from that exact tissue), essential for training structure-to-function models Structure-to-Function (Prediction): A hypothetical machine learning approach that would predict neural activity patterns from static structural brain images (connectomes) and molecular annotations, similar to how speech recognition learns to convert audio to text |

|---|

Modern AI systems serve as a great example. Take Whisper, a voice transcription app. It was trained on 680,000 hours of audio paired with text. After enough examples, it can transcribe new speech, even in noisy settings or with unfamiliar accents. It learned the links between audio and text.

Just as Whisper learned how sounds match words, we may find that neuron structures imply activity patterns. Architectural motifs and molecular labels might reliably predict neural dynamics. Invisible to humans, but detectable in massive datasets.

Holler et al. (2021) shows the promise of this approach. They combined slice electrophysiology with electron microscopy in the mouse somatosensory cortex. The result was that the size of synapses can predict their functional strength. This suggests that structure can indeed reveal insights into function. It's unclear how well these algorithms generalize across individuals, brain regions, or species. But the goal is clear: collect lots of aligned structural and functional datasets to predict function from structure.

Figure: Structure-to-Function figure. A new step is added for training a structure-to-function translator based on aligned datasets to the pipeline. This program can then be used to later provide neuronal activity across the whole connectome.

|

|---|

So how much data do we need to train these models? For Whisper, it required 680,000 hours of audio in 30-second segments, totaling around 20 million examples.

Structure-to-function models need datasets that are large and diverse enough to matter but still practical to build. This could look like the following. Record two small brain volumes per animal, each about 1 mm³. One is an “anchor” region chosen from a fixed list that repeats across animals. The other is an “explorer” region that rotates through the rest of the brain to fill coverage. For each volume, record neural activity at high speeds of at least 200Hz like voltage imaging for about 10 hours. Sample resting, natural movement, visual, auditory, and orofacial contexts. Then collect a richly molecularly annotated connectome using expansion microscopy pipelines.

Repeated anchors let the model compare individuals and generalize to new animals. The explorer volumes ensure that all cell types and microcircuits across the whole brain are covered. At the fast end a model learns from short millisecond windows that capture quick neuron-to-neuron interactions. In parallel it ingests longer contexts, 5 to 90 seconds, that carry state and behavior. It sees individual neurons, small microcircuits, and the full 1 mm³ cube. Such a setup would be fairly similar to how modern machine learning models ingest other data formats.

Similar to scaling laws in AI, more data will likely result in better results. But without exploratory studies and trendlines, we can't grasp this relationship well. We can't say whether a feasible structure-to-function prototype will arise at 100, 1,000 or 10,000 mm3-hours. The sampling plan needs to be revisited after the first 10, 25, and 50 animals to adjust.

MICrONS invested $100M to create the first 1 mm³ aligned dataset of a mammalian brain. Most of that money was spent on acquiring the connectome. Combining lower acquisition costs, cheaper connectomes, and better recording methods might cut costs down to about $0.5 to $5 million per mm³.

My calculations / budgets are illustrative and warrant much deeper analysis. Maybe much could already be learned from straightforward simulations or much smaller neural tissue petri dish experiments. Structure-to-function remains a theory to be tested. It might fail entirely for data acquisition challenges or theoretical shortcomings. And there are many challenges and good reasons to be skeptical. Neurons easily span multiple millimeters. Capturing cross brain area interactions will accordingly be error prone at best. Dynamic molecular annotations for neuromodulators and hormones are really challenging to capture. And capturing complementary brain states will be no easy task. As far as I can tell, it still remains our most promising path forward.

Closing the Non-Neural Gap: Modeling Hormones, Glial cells, and vasculature

The earlier faithfulness criteria included “diverse neural and non-neural cell types” and “interacting modulatory systems."

Neuromodulator: Chemical messengers (like dopamine, serotonin) that modify how neurons respond to signals. They operate more slowly and broadly than direct synaptic transmission. Glial Cells: Non-neuronal support cells in the brain. They outnumber neurons and perform functions like maintaining brain environment, providing metabolic support, and modulating synaptic activity. Behavioral Data Collection: The systematic recording and measurement of an organism's actions and responses (such as movement patterns, decision-making, sensory responses, or learning). Generally this is synchronized with neural recordings to understand the relationship between brain activity and behavior. Neuromorphic Computing: A computing approach that mimics the architecture and operating principles of biological neural networks in hardware. Such brain-inspired chips might offer more efficient ways to run brain emulation models |

|---|

These environmental co-variates and non-neural components are as far as I can tell are underexplored. Accordingly neither of the above mentioned factors is incorporated in today’s brain emulation models.

For the report we looked into the labelling of hormones and neurotransmitters. At the frontiers of such neuromodulation research genetically engineered cells glow when a certain molecule binds to a cell. But so far no reliable ways exist of tracking their location over longer periods of time.

Glial cells are believed to primarily serve as support engines for neurons. We see non-neuronal cells in connectomics scans, and trace them and potentially highlight their molecules if necessary. But so far this has not happened on a connectome scale and our understanding of their effects on computations are limited.

Neuromodulators and glial cells are highly important and understudied examples a complex nervous tissue that we are far from understanding completely. A good opportunity to acknowledge a broader point: there might be factors beyond neuronal activity, connections, and their molecular annoations that we don’t know today, but might discover in the future. We should address these uncertainties both, by studying them in greater detail and being conservative with projections for successful brain emulation models.

V. Potential Next Steps for Brain Emulation Models

| In short: Next steps for Brain Emulation models

A breadth of opportunities exist spanning many fields and orders of magnitude in funding. A well-validated insect-sized brain emulation model could be ready in 3-8 years with an investment of $100M or more. With this amount, current recording and scanning technologies can generate nearly ideal whole-brain datasets from 50-100 individuals. A model trained on such a dataset would set a ceiling on today's emulation abilities and clarify the data needs for larger brains. Larger brains first require evidence for “automated” proofreading and structure-to-function working. Molecular barcoding efforts to overcome proofreading are ongoing. Parallel initiatives could generate more proofread training data. The costs for proofreading thousands of complex mouse neurons is likely in the tens of millions of dollars. A first mouse connectome could then costs $200-300M, a marginal one $50-75M. Further cost optimizations are plausible. To assess structure-to-function prediction accuracy comprehensive programs are needed. They should perform scaling studies for factors like volume-recording hours and molecular annotations. Durations of 3-5 years and $50M to $100M seem plausible. Various highly tractable fieldbuilding opportunities exist could start off with less than $5M in funding. This paves the way for attracting talent and further funding. |

|---|

The range of actions needed to achieve better brain emulation models is vast, from fieldbuilding to R&D, from thousands to billions of dollars. I've compiled a non-exhaustive list of ideas in the table at the end of this chapter. If you end up taking one up, you may be one of only a few, or even the only person, working on any of these ideas. It's still early days for the brain emulation pipeline.

For the purpose of this chapter I want to zoom into the activities I consider necessary preconditions for starting work on faithful human scale brain emulation models.

To recapitulate, the target level of biological faithfulness I defined as:

Verified wiring diagram of all neurons

Diverse neural and non-neural cell types

Complete growth and pruning of neuron connections

Detailed multi-compartment neuron models

Interacting neuro-modulatory systems with feedback

Millisecond time frames

Embedding the digital brain in a virtual body

At this point, humanities’ capabilities are approaching data acquisition and modelling required for faithful brain emulation for sub‑million‑neuron brain emulation models. This includes adult insects or developing vertebrate brains. It’s still a stretch, but increasingly tractable given todays’s technologies.

Mouse-sized brain emulation models (around 100M neurons) remain orders of magnitude beyond current capabilities without further technological breakthroughs. In particular, as per our information rate figure from the previous chapter, we may need to wait 20-50 years for whole-brain recording tech to match whole-brain connectomics.

With human-sized brain emulation models these naive timeline extrapolations shift further. Even if with exponentially falling costs similar to Moore’s law, bridging three orders of magnitude from mouse to human takes time, roughly 20 years. If trends are more similar to super-exponentially falling costs like DNA sequencing it might be less than a decade. But since many technological shortcuts like genetic engineering (molecular annotations and single-cell fluorescence recording) or ethical constraints for invasive recordings don't translate to humans, I would err on the side of conservative estimates. My optimistic projection, assuming generous funding for the intermediate steps and no major hiccups, is a mouse brain emulation model in the mid 2030s and human in the late 2040s. My more conservative estimate adds 10-20 years to the mouse, 20-50 years to the human estimate.

Accordingly, we will dive into:

Faithful sub‑million‑neuron (SMN) brains emulation models: In an fairly unconstrained data collection environment, understand the neuron and non-neuron data needs for faithful brain emulation models. Achievable in 3-8 years; estimated budget ~$100M.

Human-free neuron reconstruction: Eliminate all manual human involvement in reconstructing digital neurons from tissue scans, in particular proofreading. Achievable in 3-5 years; estimated budget $5-50M.

Structure-to-Function feasibility studies: Demonstrate that (annotated) connectomes in conjunction with structure-to-function models are sufficient for faithful brain emulations. Achievable in 2-10 years; estimated budget ~$50-100M.

Notably missing here is hardware development, which I expect will happen on its own due to AI and general computing trends. Note that all my budget recommendations generally assume centralized efforts that consolidate talent and infrastructure.

I conclude with a fourth opportunity that refelcts what me and my colleagues tried to achieve with the State of Brain Emulation 2025 Report and this guide:

Fieldbuilding and knowledge curation: create clarity, removes barriers, ensures high levels of rigor and pave the way for great talent doing reputable work on a brain emulation. Achievable in 2-5 years; estimated budget <$5M.

Sub‑million‑neuron Brain Emulation Models

Faithful brain emulation of insects or larval fish is within reach. These models can validate brain emulation approaches at much lower-cost than mammalian brain models. Current recording and scanning technologies can generate increasingly better, cost-effective, whole-brain datasets. Insect brain emulation models set a ceiling on today's emulation abilities. We are unlikely to get anywhere as good or as much data for bigger organisms and can leverage the ability to collect almost arbitrary amounts. Also, the eventual availability of whole-brain recordings in sub-million-neuron organisms can test the structure to function hypothesis. Parts of data can be held out and degeneration of the model observed. All of this will clarify the eventual data needs for larger brains.

The organism of choice likely is the fruit fly or larval zebrafish, as they already have an existing neuroscience community and more generally a wealth of genetic tools. Eventually sub-million-neuron organisms also covers more economically relevant organisms like honey bees or mosquitos. Honeybees are affecting 5-8 percent of global crop production, account for hundreds of billions of dollars, while mosquitos have devastating effects transmitting Malaria/Dengue. Their brain models could be the first with real economic impact and investment returns.

A miniature version approach could be a neuron tissue culture brain emulation model. Instead of an organism, grow neurons in petri-dishes and do analyses there. This comes with many benefits, although I personally strongly prefer an actual organism and its behavior over artificially “trained” neuron tissue cultures.

Table: Conditional Budget Estimate for an Insect Brain Emulation Model. Estimates for up to 1 million neurons.

| Faithful Emulation category | Line Item | Budget Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Verified wiring diagram of all neurons | Connectome ExM (average ExM molecular annotated connectome) | 1M |

| Diverse neural and non-neural cell types | ||

| Detailed multi-compartment neuron models | 50 whole-brain recordings with perturbations and aligned datasets over 3 years | 25M recordings, 50M for Connectomes |

| Millisecond time frames | ||

| Embedding the brain in a virtual body | Estimate embodiment development and neuromodulatory experiments | 10M |

| Complete growth and pruning of neuron connections | Partially covered by recording experiments. Additional experiments of unknown scope likely necessary | ? [highly uncertain - no guess] |

| Interacting neuro-modulatory systems with feedback | Partially covered by molecular annotations. Additional experiments of unknown scope likely necessary | ? [highly uncertain - no guess] |

| Hardware for a brain emulation model | Negligible | |

| Buffer (20%) | 15M | |

| Total | ~100M |

Human-free Proofreading and a Mouse-Scale Connectome

According to our calculations in previous chapters, proofreading dominates timelines and costs of a first connectome. As you now know, work to address this is already in progress.

A complementary approach could gather more proofreading training data. Much of the connectomics image data remains un-proofread. Ongoing efforts keep gathering more image data. Every additional proofread neuron can serve as a data point for machine-learning training. A “proofreading organization” could accelerate this process. Targeted proofreading of neurons where algorithms currently struggle the most promises better algorithmic performance. Assuming a focus on the more complex neurons, thousands of additional examples could be collected, if millions are invested23. Such an effort could greatly improve models, up to matching or even surpassing human levels. It would also add immediate value to existing scientific efforts. Beyond, further applications of AI, e.g. self-supervised learning, remain underexplored in relative terms.

Proofreading costs might drop enough over the next 3 to 6 years to tackle larger brains. Key figures behind E11’s barcoding recently suggested that three years and $150 million might get us multiple connectomes. Their budget estimates differ slightly from the ones I presented. Using the numbers from my budget, costs look more like $200 million for the first and $300 to $500 million for multiple. But depending on how optimistic one sets the budget’s setting, it could be half this. So, the idea is similar: a well-funded project might achieve a mouse connectome soon.

Structure-to-Function Models Feasibility Studies

The feasibility of the previously outlined structure-to-function hypothesis remains a major uncertainty in mammalian brain emulation models. A dedicated program should clarify: